Patent litigation changed with passage of the America Invents Act. Overnight the PTAB became a new venue for challenging patent claims using IPRs, CBMs and PGRs. The initial reaction by the patent bar to the PTAB’s “take charge” approach to instituting review and canceling patent claims was met with approval by businesses under attack by patent trolls and with disdain by patent owners whose patents would have likely sailed through the assertion before the AIA. Some commentators blasted the PTAB for a high percentage of patent claims invalidated in PTAB proceedings.

Those who tried to paint the actions of the PTAB with a broad brush in the first years of IPRs were bound to be both right and wrong. Yes, institution rates were at an all-time high, but factors such as these made the first years of PTAB practice particularly hard to characterize:

- the patent bar and the PTAB were learning how to litigate these new patent trials for the first time;

- litigation teams did not have the luxury of seeing how the PTAB viewed patents under review, and to tailor their litigations accordingly; and

- a number of patents already in litigation were selected based on a pre-AIA (pre-IPR) enforcement economic model:

- discovery and litigation costs established a minimal nuisance settlement value (now it is the cost of IPR);

- thinly capitalized patent owners who previously had to outlay only minimal investment in the litigation suddenly had to secure counsel to defend patent rights in these patent reviews for the first time; and

- the patents under review were drafted to survive district court scrutiny and enjoy the presumption of validity and a clear and convincing standard of review (and many still are).

Public sentiment was a moving target, but so was practice before the PTAB. After witnessing the PTAB’s heightened scrutiny of patentability, rather than file new suits many patent owners decided to wait and watch from the sidelines or take their assertions outside the U.S. Regardless, patent owners quickly learned the benefit of analyzing and selecting patents more likely to survive an IPR, CBM or PGR lodged by a defendant-petitioner before engaging in a patent litigation.

Now, with PTAB institution rates moderating, it remains to be seen whether the Board is easing its scrutiny on patentability or whether higher caliber patent assertions are being lodged in view of that heightened scrutiny.

For example, the PTAB recently rendered some decisions that might give patent owners reason to reconsider:

CASE STUDY 1: IPR2016-01453 – U.S. Patent 7,358,679 – Wangs Alliance Corp. d/b/a WAC Lighting Co. v. Philips Lighting North America Corp., Paper 8, (Feb. 2, 2017)

On February 2, 2017, the Board denied the ’679 IPR Petition filed by Petitioner Wangs Alliance Corp. (“WAC”) challenging Patent Owner Philips’ Lighting patent. The backstory of the dispute between Philips and WAC is quite interesting:

Philips has been embroiled in patent litigation with WAC since May, 2015. Koninklijke Philips N.V. et al. v. Wangs Alliance Corporation, Case No. 14-cv-12298-DJC (D. Mass.). Philips sued WAC for patent infringement of eight patents (not including the ‘679 patent) relating to lighting products and systems relating to LED lighting devices. WAC filed IPR petitions on seven of the eight patents, but obtained institution of only six of the seven IPR petitions. In January 2016, the district court litigation was stayed pending the outcome of the IPRs.

WAC later filed two IPR petitions against the ‘679 patent. The ’679 patent does not appear in the litigation documents, but WAC identified it as claiming priority to U.S. 7,352,138 (which is in the litigation) and as related to U.S. 7,039,399 (also in the litigation).

The ‘679 patent relates to an LED-based lighting unit that resembles a conventional MR16 bulb having a bi-pin base connector configured to engage mechanically and electrically with a conventional MR16 socket. Claim 1 is representative:

1. An apparatus, comprising:

at least one LED;

a housing in which the at least one LED is disposed, the housing including at least one connection to engage mechanically and electrically with a conventional MR16 socket; and

at least one controller coupled to the housing and the at least one LED and configured to receive first power from an alternating current (A.C.) dimmer circuit, the A.C. dimmer circuit being controlled by a user interface to vary the first power, at least one controller further configured to provide second power to the at least one LED based on the first power.

WAC’s ’679 IPR petition was denied when the Board adopted a claim construction of “alternating current (A.C.) dimmer circuit” that was narrower than the one proffered by Petitioner WAC.

WAC argued that “A.C. dimmer circuit” means “a circuit that provides an alternating current (A.C.) dimming signal.” WAC further asserted that it requires only receipt of an A.C. signal and the provision of power (A.C. or D.C.) to a light source. Patent Owner Philips countered that “A.C. dimmer circuit” requires an AC output from the AC dimmer circuit. The Board agreed with Philips, based on arguments and claim constructions from a related IPR (IPR2015-01294 which relates to U.S. 7,038,399), and because Patent Owner argued that “every instance of “A.C. dimmer circuit” in the ’679 patent’s specification describes an A.C. output from the A.C. dimmer circuit. (See Prelim. Resp. 4–5.)

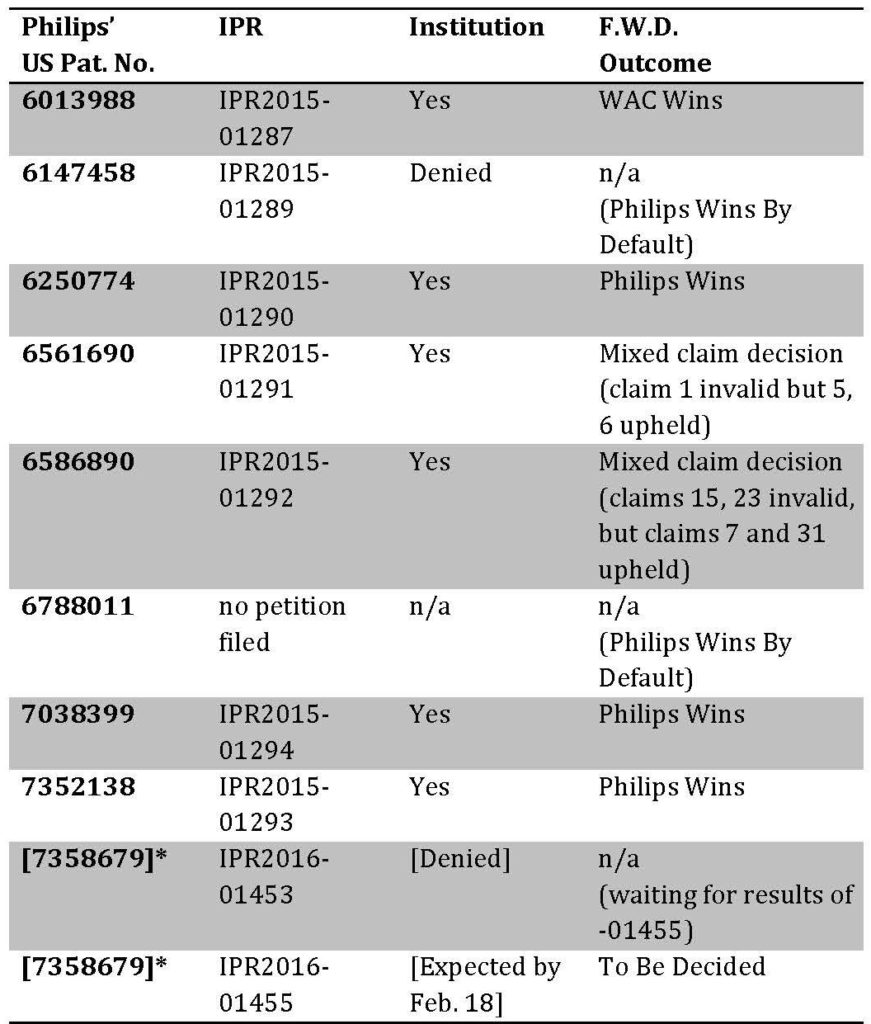

A summary of the Philips patents and their IPR outcomes thus far (note: several decisions are still on appeal) shows that Patent Owner Philips is defending its patents well in these proceedings:

* The ’679 Patent is not appearing in litigation documents, but a claim of priority from U.S. 7,352,138 and a relationship to U.S. 7,039,399 is noted in WAC’s petitions. The ’679 IPR outcome is not yet determined because even though the -01453 IPR petition was unsuccessful the -01455 IPR institution decision remains to be decided and is not expected until later this month. Note: several of these decisions are on appeal, so these are not final results.

Philips’ IPR results are comparable to historical statistics when it comes to the number of IPRs instituted, but its results are substantially better than the statistical outcomes associated with IPR final written decisions from 2016 data. For example, early Board practice saw a very high percentage of IPR institutions (starting at ~90% in 2013 and dropping to ~70% in 2016). Upon institution, a patent owner’s chances of losing all claims if the IPR were to reach a final written decision would be roughly 70%.

In this Philips case study, the percentage of IPRs instituted remains relatively consistent with IPR institution outcomes (ignoring the ‘679 IPRs because they are not yet final, we get 5 out of 7 IPRs were instituted or ~70% ); however only one of the institutions resulted in a cancellation of all claims, which is much closer to 17% than the 2016 expected 67% cancellation rate for IPRs instituted which end in a final written decision (again, the results of the Federal Circuit appeals will not be known for some time). However, the data also shows a mixed claim decision outcome in 2 out of 6 IPRs (~33%), which equates to roughly double the typical percentage of mixed claim decisions (typically ~15%). Of course, mixed claim decisions are very hard to evaluate, because one has to know which claims are more likely to be infringed with substantial damages to know if the mixed result was a winner or a loser for a patent owner.

The Philips patent IPR outcomes are not yet final, but as of today Philips is substantially ahead of the 2016 percentages.

Let’s consider another case study:

CASE STUDY 2: IPR2015-01769, — U.S. Patent 7,793,433 — Zero Gravity Inside, Inc. v. Footbalance System OY, , Paper 49, (Feb. 3, 2017)

Footbalance System OY sued Zero Gravity Inside, Inc. et al. alleging patent infringement in May, 2015 and filed amended complaints, including a third one filed on October 21, 2016. Footbalance alleged patent infringement of its US Patents 7,793,433 and 8,171,589. The patents related to apparatus and method for producing an individually formed insole.

In response, Zero Gravity filed two IPR petitions challenging claims of each patent on August 19, 2015. Both IPR challenges failed.

The ’589 IPR petition alleged obviousness of claims 1-3, but was not instituted in a Decision Denying Inter Partes Review dated January 13, 2016 (IPR2015-01770, Paper No. 17, January 13, 2016).

The ’433 IPR petition was instituted based on alleged obviousness of claims 1-7, but on February 3, 2017, the Board found that Petitioner Zero Gravity failed to show by a preponderance of the evidence that claims 1-7 of the ’433 patent were unpatentable under 35 U.S.C. § 103. Footbalance managed to maintain its claims despite institution of the IPR.

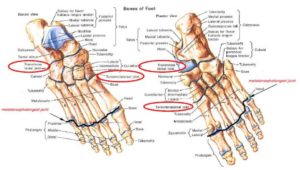

The Board decided Petitioner failed to show that the prior art taught “wherein the at least one layer of thermoplastic material is configured to reach out from under a heel of a foot only to the metatarsophalangeal joint of the foot”, as recited in Claim 1 (“the MTP limitation”).

According to the Final Written Decision, Petitioner first asserted that the MTP joint extended approximately ¾ of the way down the foot, but Patent Owner countered that a person of skill in the art would understand the MTP limitation requires a precise anatomic location of the MTP joint and not an approximation or average, such as ¾ the length of the foot. The Board found that Petitioner then shifted its argument to assert that the prior art, which taught a pad before the ball of the foot was “so close to the requirements of the MTP limitation that the MTP limitation would still have been obvious to a POSA in light of either of these teachings.” Paper 48, 8-9 (italics in original). The Board was not persuaded:

Petitioner’s contentions in the Petition are not persuasive because they are not based upon the broadest reasonable construction of the MTP limitation. As discussed above, we construe the MTP limitation to require a layer formed to extend to, but no further than, the location of the MTP joint of a specific foot. [ ]. Petitioner, however, does not sufficiently show that an insole having a ¾-length moldable support layer teaches a layer formed to extend to, but no further than, the location of the MTP joint of a specific foot. [ ]

Petitioner’s contentions in its Reply also are not persuasive. Dieckhaus discloses that thermoplastic layer 6 “extends from the back or heel portion of the insole, to approximately just short of the ball section of the foot” [ ]. Approximately just short of the ball section of the foot is not the location of the MTP joints (i.e., the location of the heads of the metatarsal bones and the corresponding proximal phalanx). [ ] Further, Petitioner does not sufficiently show that it would have been obvious to one of ordinary skill in the art to modify Dieckhaus’s thermoplastic layer 6 to extend to, but no further than, the location of the MTP joint of a specific foot. Petitioner’s assertion that such a modification would have been obvious because Dieckhaus’s disclosure is “so close” is a mere conclusory statement. “To satisfy it burden of proving obviousness, a petitioner cannot employ mere conclusory statements. The petitioner must instead articulate specific reasoning, based on evidence of record, to support the legal conclusion of obviousness.” In re Magnum Oil Tools Int’l, Ltd., [cites omitted].

The Footbalance litigation is still in its very early stages, so it is too early to tell how the litigation may turn out, but the Board did not cancel claims from either patent.

These recent outcomes do not establish a trend, but they do show that some patent owners are succeeding despite the heightened scrutiny of PTAB proceedings. They also show that the PTAB will provide relief to patent owners at both institution and final written decision stages of the PTAB trial. They also give lessons on better patent drafting, which will be the subject of future posts.

Leave a Reply